India, again.

I visited here once before. The following is the gist of a letter I sent to friends after that LAST visit. I want to see how my impressions change this time.

1995

I saw India mainly through the eyes of V.S. Naipaul, one our best living writers. Though removed from his ancestral land by 100 years and half a world, Naipaul was compelled to brutalize India in his 1964 book, An Area of Darkness. He was condemned by many for a too critical analysis. Salmon Rushdie said that visiting India ruined Naipaul as a writer.

In 1976 Naipaul revisited the same themes in India: A Wounded Civilization. Still critical, but less so.

Naipaul is clean, precise, completely unsentimental. Maughmy. His observations ring true.

Indians defecate everywhere. They defecate, mostly, beside the railway tracks. But they also defecate on the beaches; they defecate on the hills; they defecate on the river banks; they defecate on the streets; they never look for cover. … the one thing we can and must learn from the West is the science of municipal sanitation.

They do uncoil anywhere and everywhere. It is a great mingling of cow, dog, goat and human faeces. Shit dust is in the air.

I don’t mention the other usual noxious filth, open sewers, the mountains of spent trash.

Where are the sweepers? Where are the Children of God?

And disease. I just left Gujarat State where BLACK PLAGUE broke out in ’94. The government advisedantibiotics, flight, and prayer.

What personally irks me is the amount of eye disease here, of every disgusting variation. I’m told that much of this is avoidable. I saw a shapely Hindu woman walking my way — and the progressive women of Bombay are allowed to look at and even smile at tourists. I hoped to meet her gaze. As she approached I saw that one eye socket was empty.

You can imagine how I appreciate the public hawking, farting, snotting, and nose picking. Loud and proud.

I entered the National Bank in one small town; employees were spitting gobs of red betel nut on the floor.

I agree with Naipaul that Hinduism is failing India in this modern age. (I much prefer tolerant Buddhism.) Massive inefficiency, nepotism, and injustice due to the Caste System persist. Fatalism is evident; people put up with their lot in hope of reincarnation to a higher caste. Marriage is still arranged by family within caste, even among the urban educated elite.

The Indian government practices reverse discrimination, allotting jobs to specified low castes. Well-intentioned but, reportedly, problematic. Seventy upper caste students burned themselves to death in protest during a highly publicized one-week period. (One low caste entrepreneur went door-to-door in the ritzy neighbourhoods selling fire extinguishers to worried parents.)

Naipaul relates the story of a foreign businessman who educated his intelligent untouchable servant. On leaving Delhi, the businessman placed the servant in a good job. On his return he found the man back cleaning latrines. The servant had been boycotted by his clan, barred from his smoking group in the evening. Alone and unable to marry, the man was forced back to his God-allotted caste.

Widow burning? Yes. And thousands of wives die inkitchen fires every year. The husband upgrades to a new wife and another fat dowry.

Naipaul painted a depressing picture: over-population, pollution, urbanization, persecution of minorities.

The tourist is harassed by touts, hacks, and beggars. Every second encounter with an Indian is a scam. Every financial contact an attempted rip-off. Even government officials short-change.

But then I thought that I had over-estimated Naipaul. His argument is eloquent, persuasive but, perhaps, wrong.

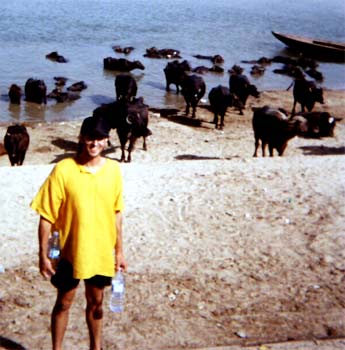

I arrived first in mystical Benares (Varanasi), holiest and most disreputable city of India, pilgrimage site of the dying. And me in the midst of some mid-life death and aging fixation. Where better to throw myself on a pyre?

Yet I had the opposite reaction. I became Mr. Gregarious, in love with life. Some kind of zealous minor prophet. A Jewish-Canadian yoga hippie and I spent a day being nice to hawkers and beggars. (What’s your name? How are you doing? Where do you live?) He rang a bell to cleanse the air of ill-feeling.

Our strange behaviour attracted the attention of a cool Indian sadhu and soon found ourselves in the Ghat Ashram of an equally cool Swiss-French Guru. We smoked a ritual bong and talked bullshit spiritualism for hours. These Hessian journeyers seek something higher and find, usually, diarrhoea. India does, though, seem to bring out the noble best in Western travellers. It did for me.

These sadhus look great; ganja-eyed, painted, flowered, bangled, seeded and beaded; dreadlocks, rags, and fierce tridents for the Shivites. I have a guarded respect for the true Holy men of Hinduism, some of whom are officially declared dead by the courts before setting out. One ascetic did not leave his cave for over 50 years. Many sadhus, unfortunately, have fled debt, the law, or their families who are often left helpless.

These sadhus look great; ganja-eyed, painted, flowered, bangled, seeded and beaded; dreadlocks, rags, and fierce tridents for the Shivites. I have a guarded respect for the true Holy men of Hinduism, some of whom are officially declared dead by the courts before setting out. One ascetic did not leave his cave for over 50 years. Many sadhus, unfortunately, have fled debt, the law, or their families who are often left helpless.

At the Ashram a woman from Boston told us that they use the term sadhu loosely in Benares. Here it means anyone who hasn’t had sex yet today. She told us that American women with gold cards like to hang here with their Indian Gurus. I wondered if she was one of these sexual adventuresses.

I started listening to Enigma and lighting incense. I read on India.

India is impossible for a list-making sort. (Those who would have things organized in India might, as well, try to straighten a winding road.) There is no reliable information. Nothing is up-to-date. Yet in my new found Buddhist acceptance, I simply embraced the non-system. Nothing works in India and yet millions get where they are going anyway. OK.

These sadhus look great; ganja-eyed, painted, flowered, bangled, seeded and beaded; dreadlocks, rags, and fierce tridents for the Shivites. I have a guarded respect for the true Holy men of Hinduism, some of whom are officially declared dead by the courts before setting out. One ascetic did not leave his cave for over 50 years. Many sadhus, unfortunately, have fled debt, the law, or their families who are often left helpless.

These sadhus look great; ganja-eyed, painted, flowered, bangled, seeded and beaded; dreadlocks, rags, and fierce tridents for the Shivites. I have a guarded respect for the true Holy men of Hinduism, some of whom are officially declared dead by the courts before setting out. One ascetic did not leave his cave for over 50 years. Many sadhus, unfortunately, have fled debt, the law, or their families who are often left helpless.